WIN 1 of 4 copies of powerful new YA non-fiction collection, Allies

Read an exclusive extract from Allies

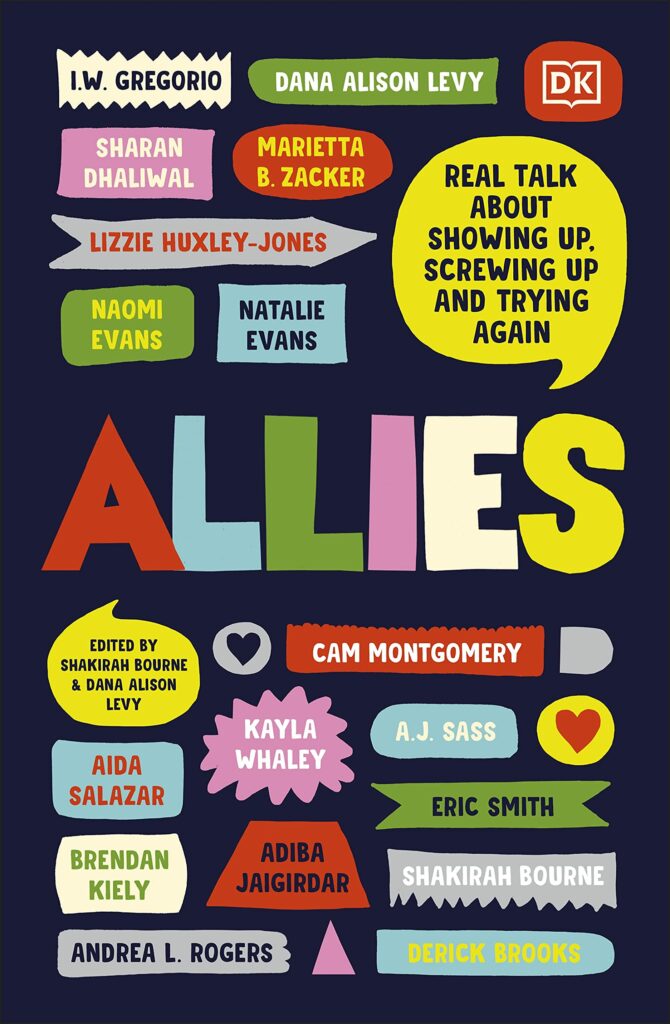

Featuring a collection of true stories, 17 critically acclaimed and bestselling YA authors discuss what it means to be an ally in Allies, an incredible new must read for all those looking to stand up and do their part as an ally.

To celebrate this release of this powerful and important new book, we not only have the below extract of Naomi and Natalie Evans’ featured essay “Why didn’t anyone else say anything”, we also have four copies to give away to four lucky readers.

“WHY DIDN’T ANYONE ELSE SAY ANYTHING?”

Naomi and Natalie Evans

“We have to repent in this generation not merely for the hateful words and actions of the bad people but for the appalling silence of the good people.” – Dr Martin Luther King, Jr, “Letter from Birmingham Jail”, 1963

NATALIE

“It was late October and I was at the train station in London travelling back to my small hometown by the sea. It was a sunny Friday afternoon, but the air was cold enough to see the condensation from my mouth when I breathed out.

I had just finished a full day of work that involved a lot of meetings, to see, and dull conversation, so I was very tired and ready for the weekend ahead. I stood on the platform in my thick coat and a scarf, wishing I had driven that day. The clock turned 3:25, and two bright circle lights entered through the tunnel.

“Finally,” I thought. I waited for passengers to get to before I stepped on the train and found two single seats available. Then I put in my headphones, tilted my head on the glass window next to me, and closed my eyes while the train sped to to the next stop. As my podcast played I heard a faint announcement in the background as the train slowed down at the next stop.

When I opened my eyes, I saw two white men, both wearing black coats, jeans, and carrying a supermarket bag which I imagine had the remaining cans of beer that they were holding in their hands. They were speaking like they were in a nightclub, where you have to shout over the music to hold a conversation. Other passengers noticeably shuffled their bodies and moved to attention. Ears pricked up – some people looked up and away quickly while others rolled their eyes to show their disapproval at the lack of train etiquette.

All I wanted was a quiet journey home. I hoped they wouldn’t be on the train for much longer.

As I scanned the carriage once again, I noticed something that wasn’t very unusual to me; everyone else was white. I am mixed race. My dad is Black Jamaican and my mum is white British, so I have brown skin along with big curly afro hair. I grew up in a very white area in Kent where most of my life I was the only person – apart from my two sisters – that looked like me in the room.

The two men were two seats away from me. I could see them between the gap in the seats and the reflection of a man in a black jacket, still clutching his beer, in the train window. Once they sat down, I closed my eyes again, leaned back on the glass window, and tried to nap once more.

The nap didn’t last very long. I was interrupted by the booming voice of the conductor asking for tickets. I took my headphones out and pulled out my train ticket, ready for when he approached. The train conductor was a Black man. It’s not unusual for me to notice people’s race; even though my town has become more diverse and multicultural, I am still surprised when I see a Black person in the area.

I smiled and passed over my train ticket, he gave me a nod and I nodded back. This is very normal in the Black community – it’s like an acknowledgement, a code for “I see you, I understand, I get what it’s like to be Black in this world.” I watched him walk down the carriage, asking the other passengers for their tickets, and I looked at the two loud drunk men. In my gut I knew not to put my headphones back in.

You see, when you’re used to being the minority in the room you tend to pick up on certain things when in public spaces. You know when situations feel unsafe or when people are hostile towards you. You sense when to not trust a person; it’s an instinct

and it’s one that I’ve gotten very used to over the years.

The train conductor walked over to the two drunk men and said, “Tickets please.” There was silence, so he repeated, “Tickets please,” again silence. I stared at the man with the supermarket bag in between the train seats, snickering to his friend. The conductor repeated himself again, but this time his tone was agitated and short.

Finally, the man with the supermarket bag responded without looking up, “We are getting off at the next stop, mate.”

The train conductor replied, “That’s not how it works, it doesn’t matter if you get o at the next stop, you still need the ticket before getting on the train.”

This went back and forth for about 30 seconds. The conversation between them was getting much louder and at this point more people started to pay attention. My instincts were right. After the train conductor explained that they would need a ticket in order to continue the journey the man with the supermarket bag replied, “Did you get a f***ing passport to get into the country?”

It was at that point my ears pricked up like a cat when they hear it’s time for a bath. I scrambled around in my pocket, got out my phone, and pressed record.

This was my second step of being an ally.

You see, step one was realizing that this was not a safe space for the conductor. Being an ally means anticipating when someone may need support. It’s about understanding the power dynamics within a room.

The train conductor’s face dropped; he had a combination of facial expressions – shocked, angry, and embarrassed. I could see in his face he didn’t know what to do. The next five minutes were a blur; without the phone recording I don’t think I would’ve been able to remember what happened next. As soon as I pressed record, the train conductor sat down next to the two drunk men. I was very surprised when he decided to sit next to them. I wondered if it was to try and deescalate the situation, maybe coming down to their level meant that they could have a conversation, rather than standing over them intensifying an argument. He then asked in an upset and slightly angry voice, “What has me having a passport got to do with your train ticket?”

It was unclear what one of the men was trying to explain but it didn’t matter

by this point. What he had said was racist and he was not willing to apologize for it.

The train conductor’s voice got louder and his hands became more expressive. He kept repeating, “What has me having a passport got to do with your train

ticket?” He told the man that his comment was racist.

The white man responded, “I’ve got two mixed-race children and this guy thinks I’m racist.” The train conductor shook his head, gave a loud sigh, and stood up to walk away. He was finished; the man was not listening and now had brought out his get-out-of-jail-free card, his mixed-race children.

I can relate to this feeling in so many ways. Someone has said something offensive, you challenge it, but it’s game over. Defensiveness kicks in. White fragility comes into play and there is nowhere to go but to walk away. Yet, the man with the supermarket bag was still not finished. “It’s always the Black card with you innit.”

My blood was boiling. I was raging and everything inside me wanted to explode. There were so many things about this situation that were problematic but to then bring in mixed-race children and the race card? I could not just sit there and record this incident anymore, I had to say something. Before I knew it I stood up and without a thought, I opened my mouth.

This was step three of my allyship that day. I didn’t have a well planned- out speech, but the fact that no one else spoke up meant whatever I said was better than silence.”

Want more? Follow the instructions in the tweet below for your chance to win one of four copies of Allies:

https://twitter.com/unitedbybks/status/1422914606780006400?s=20

Get your copy of Allies edited by Shakirah Bourne and Dana Alison Levy here.

Get your copy of Allies edited by Shakirah Bourne and Dana Alison Levy here.