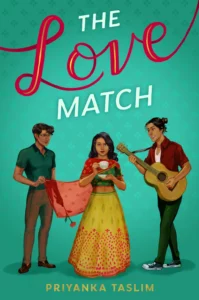

If You Love these Three Pieces of Media, You Should Read The Love Match

Priyanka Taslim shares three reasons you’ll love her adorable new YA romance, The Love Match, based on your favourite pieces of media.

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before: I’m sure I’m not the only one who misses this beautiful series now that Netflix has finished adapting the trilogy. Certainly, Jenny Han’s other series, The Summer I Turned Pretty, manages to fill some of the void Lara Jean, Peter, John Ambrose, and the entire Covey family left behind, but I often catch myself watching or reading TATB again. It was pretty revolutionary, as one of the earliest young adult novels to present an overtly Asian-American heroine as the protagonist in a YA romance, the girl so many boys are vying for.

To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before: I’m sure I’m not the only one who misses this beautiful series now that Netflix has finished adapting the trilogy. Certainly, Jenny Han’s other series, The Summer I Turned Pretty, manages to fill some of the void Lara Jean, Peter, John Ambrose, and the entire Covey family left behind, but I often catch myself watching or reading TATB again. It was pretty revolutionary, as one of the earliest young adult novels to present an overtly Asian-American heroine as the protagonist in a YA romance, the girl so many boys are vying for.

Similarly, The Love Match follows Bangladeshi-American teen Zahra Khan during the whirlwind summer before college as she’s thrown headfirst into a love triangle by her mother’s scheming. Like Lara Jean, Zahra is grieving a parent—except the loss of her father two years prior has put her family into financial precarity despite their status back in Bangladesh. While Zahra takes every available shift at neighborhood tea shop Chai Ho, owned by the father of two of her best friends, in an effort to help her loved ones and save up for college, her meddling mother decides to take a more traditional approach: setting Zahra up with Harun, the only son of the wealthy Emons, who is everything a Bangladeshi boy should be. Since neither Zahra nor Harun are interested in the match, however, they hatch their own scheme, reminiscent of Lara Jean’s and Peter’s—they’ll fake date for the summer to keep their parents happy, even as they sabotage the relationship from within. Unfortunately for Zahra, her very real budding feelings for Nayim, a charming young orphan who just started working at the tea shop, might throw a wrench in all her plans.

Modernized Jane Austen novels: People often assume The Love Match is a Pride and Prejudice reimagining, because Zahra is heroine as headstrong as Elizabeth and you have a counterpart to Mr. Darcy in the broody Harun (in this version, I suppose Nayim would be a cross between Mr. Bingley and a less awful George Wickham). In actual fact, it’s not—but it is written in the spirit of Austen’s comedies of manners, which often humorously and incisively analyzed the social politics of Regency society. After undergoing my own sometimes hilarious and misguided attempts at matchmaking while living in Paterson, I decided that I really wanted to do something similar for its Bangladeshi community.

Modernized Jane Austen novels: People often assume The Love Match is a Pride and Prejudice reimagining, because Zahra is heroine as headstrong as Elizabeth and you have a counterpart to Mr. Darcy in the broody Harun (in this version, I suppose Nayim would be a cross between Mr. Bingley and a less awful George Wickham). In actual fact, it’s not—but it is written in the spirit of Austen’s comedies of manners, which often humorously and incisively analyzed the social politics of Regency society. After undergoing my own sometimes hilarious and misguided attempts at matchmaking while living in Paterson, I decided that I really wanted to do something similar for its Bangladeshi community.

Like Regency society, Bangladeshi elders within Paterson often put a lot of stock into “suitable matches,” based on one’s family heritage and status in Bangladesh, despite being predominantly working class in America. This is slowly changing, but readers who crave the “vibes” of an Austen novel while perhaps desiring more original beats than most outright retellings will most likely enjoy The Love Match and its heroine, who The Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books called “an admirable descendant of many Austen heroines: sharp, witty, and observant as Elizabeth Bennet, youthfully short-sighted like Emma Woodhouse, but also possessing the steady character and sense of purpose of Eleanor Dashwood,” in their starred review.

Never Have I Ever: At their most basic level, Never Have I Ever and The Love Match have a lot in common. They both follow South Asian teenage girls navigating grief and feelings for multiple boys with the help of their loving-but-sometimes-annoying families and their diverse group of best friends.

Never Have I Ever: At their most basic level, Never Have I Ever and The Love Match have a lot in common. They both follow South Asian teenage girls navigating grief and feelings for multiple boys with the help of their loving-but-sometimes-annoying families and their diverse group of best friends.

However, the humor in The Love Match is less irreverent. Zahra and Devi present opposite sides of two very different coins: while Devi is obsessed with the concept of rebelling against her strict, upper middle-class mother, Zahra desperately wants to be A Good Bangladeshi Daughter™ for her remaining parent, perhaps because the stakes of messing up are so much higher for her as a girl from a working class family, particularly as the oldest daughter, whereas Devi is an only child.

Both of these narratives are equally as important. In fact, I want to see an endless amount of diverse media about South Asian girls, and Mindy Kaling’s projects are unique for letting their protagonists be deeply flawed and messy, an allowance not many brown girls are given by reality or fiction. But if you watched Never Have I Ever and seek something in a similar vein between seasons or after the final season airs, you might just find what you seek in The Love Match (especially if you want more media with brown protagonists and love interests).

Whatever you’re looking for, I hope The Love Match will be your cup of tea, because despite the things it has in common with these pieces of media, it is also something special in a world that has yet to publish a YA romance between a Bangladeshi boy and girl, much less an entire Bangladeshi love triangle and an entirely brown cast.

Get your copy of The Love Match by Priyanka Taslim here.

Get your copy of The Love Match by Priyanka Taslim here.