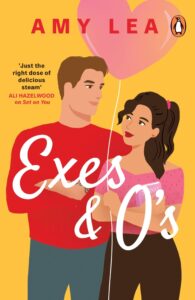

Exes and O’s author, Amy Lea, on the beauty of seeing yourself in mainstream media

"Imagine growing up to the age of 18-years-old and only ever having a handful of women in mainstream media who look like you."

This post was written by Amy Lea, author of Exes and O’s.

The 90s and early 2000s were a simpler time. Sure, my pre-teen style was questionable (thrice layered Hollister tank tops, butterfly clips, and a greasy side-swept bang). But life was good. I wasn’t glued to my smartphone, relying on likes as a barometer for validation. High-quality rom-coms were still alive and thriving. I have fond memories of evenings eating Dunk-a-roos, strewn over my plastic inflatable couch, poring over American teen magazines (Cosmo, Glamour, J-14, and Teen Bop), taking quizzes, and reading my horoscope. My poster-filled bedroom wall was practically a shrine to the women on the covers of these magazines; Hilary Duff, Lindsay Lohan, Mandy Moore, Jessica Simpson, etc. They were my idols. And they all had something in common: none of them looked like me.

Lucy Lui was the first actress I saw on television that resembled me. And by “resembled,” I mean she, too, was Chinese. In fact, the kids at my all-white school decided she was my celebrity lookalike (spoiler alert: we look absolutely nothing alike, unfortunately for me). Lui was arguably one of the only mainstream, A-list East Asian actresses for years.

View this post on Instagram

Then I discovered Brenda Song in the mid-2000s, who played a spoiled hotel heiress loosely based on Paris Hilton in Disney’s The Suite Life of Zack and Cody. Here, Song’s character wasn’t traditionally stereotyped (aside from being wealthy). Her role wasn’t about her “Asian-ness” or being a model minority. While arguably still problematic in many ways, her character had a personality, a backstory, wants, and needs – all separate from her ethnicity. And while erasing a character’s culture isn’t ideal either, keep in mind, it was exceptionally rare to see East-Asian women in film and television that didn’t fall into one of the following categories: the martial arts dragon lady, the geisha, the nerd, or the flimsy, side-character bestie with no agency.

Imagine growing up to the age of 18-years-old and only ever having a handful of women in mainstream media who look like you. I didn’t realize it as a child, but when you don’t often see yourself represented in the media you consume, you begin to think you’re not worthy of being a main character in your own life. And despite people telling you you’re “beautiful the way you are,” you’re never going to believe it if wider society doesn’t reflect that.

Here’s the thing: I always dreamed of being an author. But because I never saw myself represented on-screen or in books, it never even occurred to me to write a main character who wasn’t white. In fact, the first two books I wrote before Set On You (which will never see the light of day) featured white heroines.

I still remember that day in the bookstore when I saw Lara-Jean on the cover of To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before by Jenny Han, and Esme on the cover of The Bride Test by Helen Hoang. Until then, main character status and happily ever afters seemed reserved for white characters in traditional publishing. That was the first time it occurred to me that I could write a character who looked like me.

View this post on Instagram

Writing Crystal and Tara Chen in Set On You and Exes and O’s, half-Chinese, half-white characters, felt like coming home. Of course, being an author of color and writing characters of color isn’t all unicorns and rainbows. There’s the fact that marginalized authors are, on average, still vastly underrepresented and underpaid compared to their white counterparts in traditional publishing. There’s also immense pressure when writing characters of marginalized identities. Because people are desperately craving crumbs of representation, it puts unrealistic and unfair pressure on these writers to represent everyone. Unfortunately, much of the critique that authors of color face is from their own communities. I constantly have to remind myself that it is virtually impossible to represent an entire group of people. White authors are not expected to write books that are representative of ALL white people, so it feels blatantly unfair to place that pressure on the shoulders of authors of color.

Traditional publishing and Hollywood still have a long way to go with representation and inclusion. But I’m beyond proud to be a part (even just a tiny part) of this ripple of change. So many Asian readers of my books have reached out to me, expressing how meaningful it was to feel seen in a book, which truly makes all of the struggle worth it.

It’s incredibly important to me that young people of color in future generations see themselves as main characters in their own stories, the way I rarely did until adulthood. They deserve to see stories of main characters of color that not only defy stereotypes, but that centralize them as human beings.

That’s the beauty of representation in romance books – a genre that guarantees a happy ending. In romance, characters of color don’t have to be defined by their struggle. They get to experience joy and love. Everyone should feel deserving of an epic love story and a happily ever after, no matter what they look like.

Get your copy of Exes and O’s by Amy Lea here.

Get your copy of Exes and O’s by Amy Lea here.