Bryce Moore on writing real world events into fiction

"Still, when I set out to write a story around the American serial killer, H.H. Holmes, I wanted to do my best to find out as much about the history as I could."

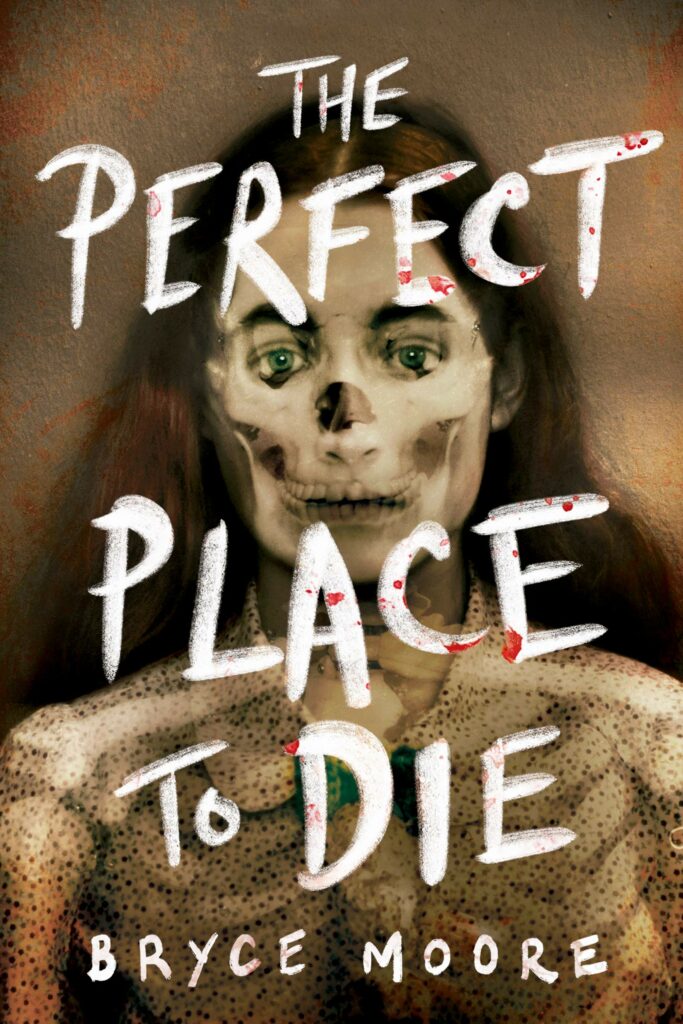

This post was written by Bryce Moore, author of The Perfect Place to Die

Whenever I finish watching a movie that’s “based on a true story,” or reading a book that’s “inspired by real events,” I typically head straight to the internet to find out what really happened. How much of what I saw or read was real, and how much was fiction? As a librarian, I like to have little research projects to keep me busy, and it’s rare I let a day go by without the compulsion to ferret out a fact or two. Having a smartphone in my pocket has only exacerbated that impulse.

Almost inevitably, when I read up on the actual events, they’re quite different from what was portrayed on the screen or page. Perhaps some characters were created from aspects of real people, or maybe certain events happened out of order or didn’t play out the way they were depicted. I’m not bothered by the fictionalization. Reality doesn’t fit itself to a narrative structure. Just because something really happened doesn’t make it a good story.

We think the past is something that can be tied down. That there’s an ultimate truth to history: find out what really happened, and then put that to paper. Theoretically, with a work that has its roots in history, all that’s left is to accurately portray those events. But that doesn’t work in practice, and the first step to realizing how impossible that seemingly simple goal is comes when you recognize history itself is an adaptation.

As a simple example, I like to ice fish. It’s a great excuse to get outdoors in the winter, and in Maine, you need to have things you love about the cold, or you’ll never want to stay. One year, I was out fishing with a friend when it started to rain. (Yes, that happens in winter, even in Maine.) Undeterred, I got out an umbrella and kept fishing: my jig in one hand and the umbrella in the other.

This worked fine until my wife called me on my new cell phone. I didn’t have enough hands to hold the umbrella, ice fish, and hold the phone, so I tucked the phone between my ear and my shoulder and talked like that—right up until I shifted my position slightly. The phone slipped down my front and splashed into the ice fishing hole. I threw down my jig and umbrella, ripped off my glove, and tried to grab it. My fingers brushed against the phone as it sank farther down, never to be seen again.

View this post on Instagram

That’s a simple story, and one that’s straightforward. There were only two people there: my friend and I. He saw what happened—he was standing next to me laughing when it did. But in the years since, I’ve heard different stories of that fishing incident. Several of his children swear they were there too, even though I’m almost positive no one else had been foolhardy enough to go out that day because of the rain. I say it was just the two of us, others say there were as many as three or four. At this point, there is no way to prove which version of that story is right.

If something as simple as that fishing expedition can be hard to pin down, imagine how difficult it is to determine what “really happened” in a war or over the course of a person’s life a hundred years ago. Even if you tried to stay true to every single detail you could find, there’s no guarantee that the reality you’ll portray bears any resemblance to the truth.

Still, when I set out to write a story around the American serial killer, H.H. Holmes, I wanted to do my best to find out as much about the history as I could. However, most of what was written about the case appeared in newspapers of the time, and reporters presented conflicting facts, usually with a tendency to print whatever would sell more papers. Holmes published a “confession” in the Philadelphia Inquirer shortly before his execution in 1896. In it, he claimed to have killed 27 people. Other sources claimed it was closer to 200. There were multiple descriptions of his infamous “Murder Castle,” but little in the way of actual photographs or detailed layouts of the building.

This was my first foray into historical writing, and I discovered everyone has to keep a balance between fact and fiction. It’s up to the creator to decide where that balance will lie. Do you want to stick as close to the truth (as you understand it) as possible? That will constrain your ability to make a great narrative. Do you want to instead lean the other way, and make it more of an “inspired by real events” tale? If you do that, then is it different than what you set out to make in the first place?

In the end, I created more a patchwork quilt out of the history around Holmes rather than an accurate depiction. I took events that had been reported, and I fit them into my plot as best I could. It gave me a much deeper respect and understanding for others who have approached the same task, and it made me realize that all history is—to one extent or another—fiction as well. We study events in isolation, and we piece those events into meaning years later.

Storytellers just tend to spruce things up a bit more than historians. For the sake of a good book, I think it’s worth it.

Get your copy of The Perfect Place to Die by Bryce Moore here.

Get your copy of The Perfect Place to Die by Bryce Moore here.